(Image credit: Getty Images)

If you ask 10 people what it means to “retire well,” most will begin by talking about money. They’ll mention savings, investments, portfolios or the confidence of living without a paycheck.

Financial security tends to dominate the conversation because it’s tangible, measurable and often seen as the gatekeeper to freedom.

Yet, beneath that conversation lies another, quieter one that rarely gets equal attention — the discussion about what wealth really means once the daily rush of earning has ended.

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more – straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice – straight to your e-mail.

Money and wealth appear to be contradictory, but in fact, they’re complementary and synergistic. The paradox between them is simple to describe and difficult to live out: Focusing on one without the other can leave us either cash-rich but impoverished emotionally or loved but insecure.

In other words, money and wealth aren’t the same. Money can buy ease, but it can’t buy meaning. Wealth, by contrast, reflects a life organized around relationships, health, contribution and time — qualities that compound differently than a mutual fund.

When the narrative changes

During our working years, money often serves as a measure of progress. It rewards effort, validates achievement and promises safety.

Yet, when retirement arrives, the narrative changes. Those external benchmarks gradually fade, and the question, “Do I have enough?” subtly transforms into “Who am I now?” This is the pivot point in the psychology of retirement — the moment when security naturally gives way to significance.

Some people enter retirement financially secure yet unprepared for the psychological transition that awaits them. They have the means to live comfortably but often lack the mindset to navigate the loss of structure and purpose that once defined their days.

Time — previously managed in fragments — now stretches unbounded, confronting them with nagging questions about identity and worth. What was imagined as freedom can, paradoxically, feel confining.

Without a renewed sense of direction (identity and purpose), the absence of professional demands leaves space that emotional readiness must learn to fill.

Emotionally wealthy but financially exposed

Others come to retirement with deep relationships, strong community ties and generous spirits — yet they live with underlying anxiety about their financial footing. They’re emotionally wealthy but financially exposed. Both sides of the paradox create stress, and each demands reconciliation.

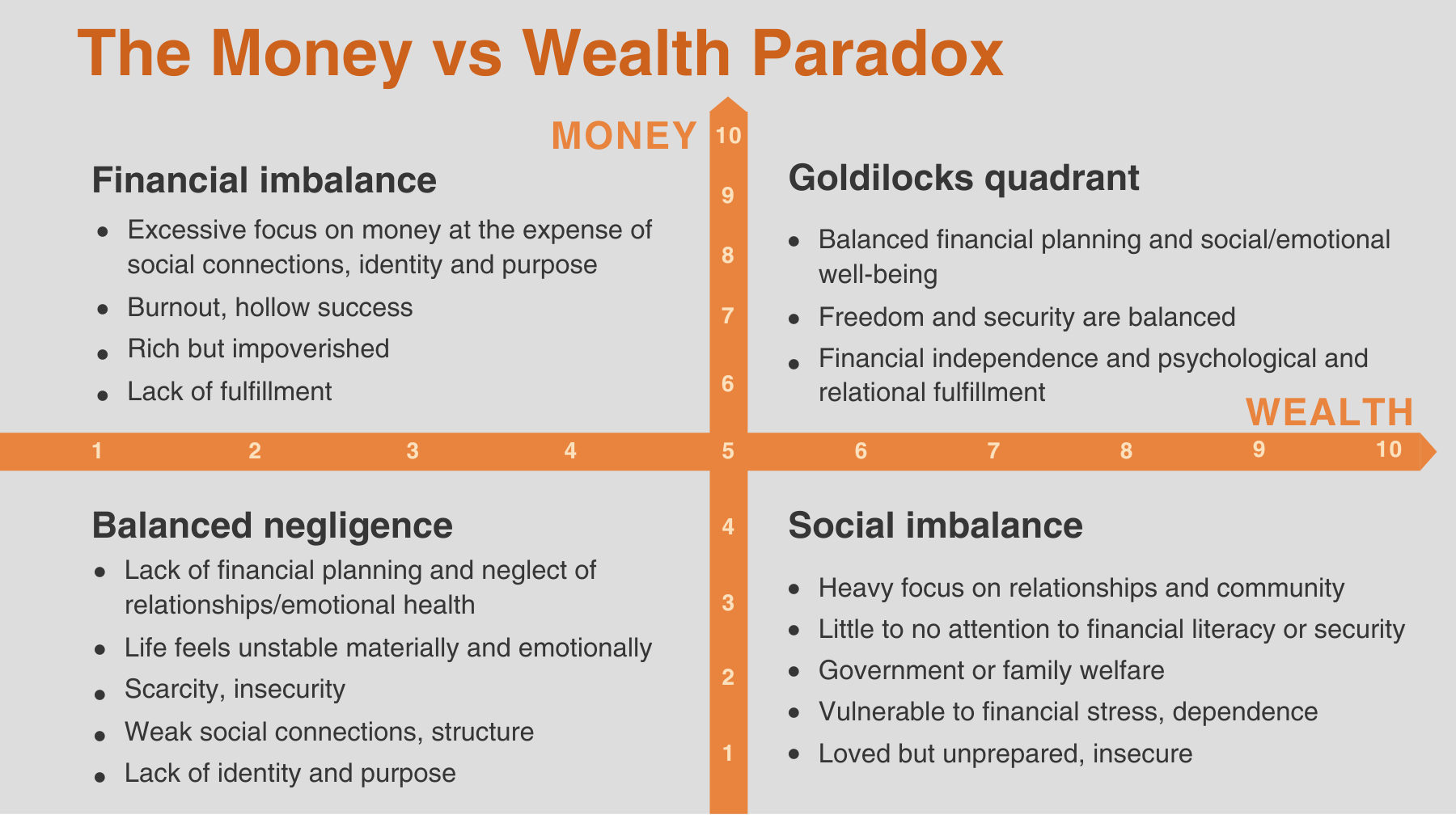

The Money-Wealth Paradox serves as a visual to illuminate this (im)balance:

The vertical (y) axis represents money: financial planning, preparedness and material security. The horizontal (x) axis represents wealth: relationships, emotional health, meaningful time and a sense of belonging.

The upper-right quadrant — the Goldilocks zone, where both are strong — is the space of flourishing, the place in which financial freedom supports emotional abundance.

The lower left, where both are weak, is a zone of scarcity — financially fragile and emotionally thin.

The two remaining quadrants express imbalances: One dominated by achievement without connection (“rich but impoverished”), the other by warmth without stability (“loved but insecure”).

Time to evaluate

The purpose of this paradox awareness is not to judge but to reveal. It asks you to evaluate whether your resources — emotional, social and financial — work together or compete against one another.

Many people unconsciously sacrifice one dimension while pursuing the other, believing they can strengthen the weaker side later. As the years pass, the imbalance tends to deepen.

The irony is that most of what we call “financial planning” was never about money. It was about emotion — security, control and freedom from fear. Investors chase returns because they want peace of mind, not because they crave numbers on a statement.

Likewise, when relationships falter or purpose is elusive, no portfolio can replace the feeling of belonging or contribution. The deeper psychology of retirement rests on uniting these inner and outer forms of capital.

Money is the language of certainty, while wealth is the dialect of meaning. Too much of the first creates pressure; too much of the second, without planning, creates anxiety. The healthy life — and the fulfilling retirement — lives in the creative tension between the two.

Integrating money and wealth

It helps to think of money as the tool and wealth as the experience. Money builds the structure; wealth fills it with life. Money can buy time; wealth determines how that time feels and is filled.

In our working years, these two often compete, but in retirement, they must integrate. Without money, experiences collapse under stress. Without wealth, financial success rings hollow.

This paradox also reveals another fascinating shift: The transition from “should” to “ought.” During the career phase, the script of life is filled with “shoulds” — what you should earn, how you should act, what you should accumulate.

Retirement challenges that external, subjective voice. It invites the language of “ought” — the inward compass that points toward meaning, contribution and alignment.

The balance between money and wealth can’t emerge until “should” yields to “ought.” Only then does choice replace obligation, and freedom begins to mature into purpose.

How do you begin to live inside this balance? The first step is awareness. Ask yourself two questions:

- How prepared am I financially?

- How prepared am I emotionally?

They might seem simple, but they measure very different currencies. Your financial preparation speaks to independence; your emotional preparation speaks to fulfillment. Every person’s answer traces a different route through the paradox.

An invitation rather than a failure

If you discover strength on one side and strain on the other, take that as an invitation, not a failure. You don’t need to choose between prosperity and peace. The challenge — and the beauty — of your Encore Years is learning how they can reinforce each other.

Sustained well-being requires both savings and belonging, just as a well-built house needs both structure and people to fill it.

For now, remember this: You can plan for your future without losing your soul to it, and you can pursue meaning without undermining your security. The art of retirement lies in keeping both in balance — the external numbers that safeguard your life and the internal values that make it worth living.

To learn more about this approach to retirement, pick up my new book, Your Encore Years: The Psychology of Retirement.