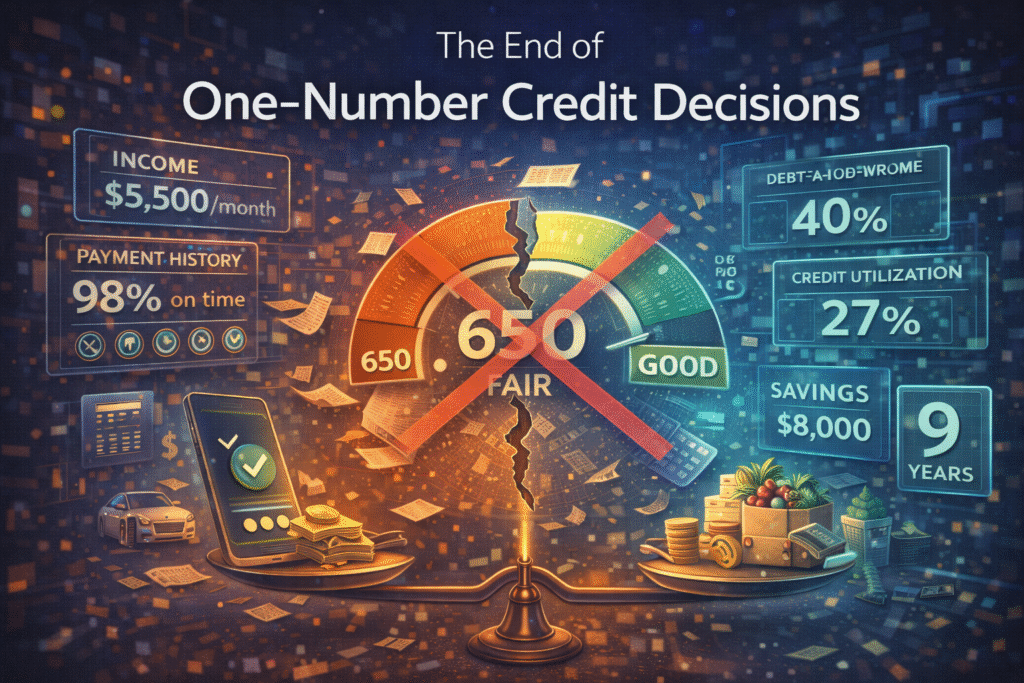

You’ve probably been turned down for credit or offered terrible terms despite paying your bills on time. Or maybe you’ve watched your score drop because of an error you didn’t even know existed on your report. The truth is, that three-digit number everyone obsesses over was never designed to capture the full picture of how you actually manage money. Credit decisions are increasingly moving beyond the credit score, recognizing that a single number can’t fully reflect real financial behavior.

The credit industry is shifting away from decisions based solely on scores and toward a more complete view of financial habits. Payment patterns over time, how you use your available credit, and even data that never appeared on traditional reports are now part of the equation. This move beyond the credit score creates real opportunities for people who’ve been held back by reporting errors, thin credit files, or outdated negative items that no longer represent their current financial reality. Understanding this change is key to building a credit profile that tells your full story—not just the part captured by a number.

Why Your Three-Digit Number Tells an Incomplete Story

Credit scoring models compress your entire financial life into a single number between 300 and 850, masking meaningful differences in how people actually manage money. This is why modern credit evaluation is moving beyond the credit score, recognizing that identical numbers can represent very different behaviors. Someone sitting at 680 might have arrived there through six years of perfect payments with one recent medical collection, while another person at the same score could have multiple maxed-out cards and a pattern of minimum payments. When decisions stay locked to one number instead of looking beyond the credit score, these fundamentally different risk profiles are treated as identical.

This compression problem becomes especially severe when credit report errors enter the equation, further highlighting why systems must evolve beyond the credit score. A single incorrectly reported late payment can drop a score by 60–110 points, regardless of whether it reflects real delinquency or a billing dispute resolved months earlier. The model cannot distinguish between a legitimate late payment and a fraudulent account under dispute. Both are penalized equally, demonstrating how reliance on one number—rather than analysis beyond the credit score—distorts actual financial responsibility.

The error multiplication effect extends beyond individual inaccuracies to create cascading damage across a credit profile. An incorrect balance doesn’t just affect one factor; it inflates utilization, triggers balance increase penalties, and may cause other creditors to reduce limits based on perceived overextension. These chain reactions further reinforce the need to evaluate consumers beyond the credit score, since the resulting damage often has little connection to real-world behavior.

Consumers with thin credit files face a different but equally flawed version of this compression. Scoring models require minimum data thresholds, leaving new immigrants, young adults, or cash-based consumers either invisible or labeled high risk despite responsible financial habits. Treating missing data as bad data exposes the limitations of single-number systems and strengthens the argument for decision-making beyond the credit score.

The timing trap represents one of the most frustrating consequences of single-score decisioning. Negative items linger for years, suppressing scores long after behavior has changed. Someone who overcame medical debt or job loss years ago may still be penalized today, even with a spotless recent record. When current responsibility is overshadowed by outdated negatives, it becomes clear that fair evaluation depends on understanding patterns beyond the credit score.

What Lenders See Beyond Your Credit Score

Trended data analysis has fundamentally changed how sophisticated credit evaluations work by revealing patterns that static snapshots cannot capture. This shift moves assessments beyond the credit score, allowing reviewers to see how balances evolve over time rather than relying on a single moment. Instead of viewing only current balances and limits, underwriters examine 24 months of monthly balance progression to understand real credit usage behavior. This approach looks beyond the credit score to distinguish between consumers who consistently pay balances in full each month (transactors) and those who carry revolving balances month to month (revolvers). Two applicants with identical 740 scores and $5,000 balances receive very different risk interpretations once analysis moves beyond the credit score and reveals their actual payment patterns.

The behavioral distinction matters because transactors demonstrate lower default risk, even when static views show high utilization. Someone who charges $4,500 on a $5,000 limit card but pays it to zero each month appears risky in a snapshot, yet trended data reveals responsible usage. Traditional models penalize this behavior without context, while systems that look beyond the credit score recognize the difference between temporary utilization and long-term borrowing. This added nuance creates opportunities for consumers whose responsible habits aren’t accurately reflected by a single number.

Granular utilization analysis further expands evaluation beyond the credit score by examining how balances are distributed across credit lines. Concentrating debt on one nearly maxed-out card signals stress, while spreading balances evenly suggests strategic credit management. These patterns remain invisible in basic scoring but emerge clearly when profiles are reviewed in depth.

Payment sequencing and recency weighting also shift attention beyond the credit score, emphasizing recent behavior over older missteps. Six months of consistent on-time payments often provides stronger insight into future performance than a single late payment from years ago. Recovery patterns—when negative activity stopped and positive behavior began—become visible only when evaluation extends beyond the credit score.

Alternative credit data integration represents the most significant expansion of assessment beyond the credit score. Rent payments, utilities, bank account stability, and income consistency provide evidence of financial responsibility that traditional reports never captured. These signals allow creditworthiness to be evaluated more completely, especially for consumers with thin files or unresolved reporting errors, rewarding real-world behavior rather than the limitations of a single scoring system.

Strategic Credit Report Management Over Score Optimization

The accuracy-first principle recognizes that correcting credit report errors delivers compound benefits that surface only when credit evaluation moves beyond the credit score. Removing an incorrectly reported late payment triggers an immediate score increase, but more importantly, it restores the integrity of your credit profile. This approach improves both the algorithmic number and the factual story lenders see during manual review, something score-gaming tactics fail to achieve when decisions increasingly operate beyond the credit score.

Disputing a single unverified collection account can result in score gains of 25–100 points, but the true advantage emerges beyond the credit score. Once the collection is removed, lenders no longer see a red flag that could trigger automatic denial. Even if other factors still suppress your number, the absence of that error improves outcomes in systems designed to evaluate borrowers beyond the credit score and prevents secondary damage like limit reductions or account closures.

The documentation advantage pushes disputes beyond the credit score by transforming them into evidence-based corrections. Detailed records—bank statements, settlement letters, identity verification—force credit bureaus and creditors to address inaccuracies substantively. When your documentation proves a reported late payment contradicts your payment history, the evaluation shifts beyond the credit score and back to factual accountability.

This documentation becomes especially powerful when disputes receive superficial responses. Consumer protections under the Fair Credit Reporting Act require reasonable investigations, not automated verifications. Submitting proof elevates the dispute process beyond the credit score, creating leverage not only for corrections but also for enforcement if reporting violations persist.

Strategic dispute sequencing further reinforces results beyond the credit score by prioritizing high-impact inaccuracies. Fraudulent accounts, mixed files, and accounts you never opened produce the largest distortions and the strongest legal footing for removal. Eliminating these items improves both numerical scores and profile credibility in systems that evaluate applicants beyond the credit score.

Once ownership errors are resolved, the focus shifts to incorrect payment histories on legitimate accounts. Because payment history represents 35% of FICO calculations, correcting false late payments yields outsized benefits. More importantly, it removes behavioral red flags that underwriters scrutinize when reviewing applications beyond the credit score.

Positive data layering complements error correction by strengthening your profile beyond the credit score. Adding new, well-managed tradelines—secured cards, credit-builder loans, or authorized user accounts—improves the ratio of positive to negative information. This dilution effect helps offset accurate negatives that cannot be removed and supports evaluation models that look beyond the credit score.

The strategic addition of positive data also demonstrates current financial responsibility in ways static numbers cannot. A profile showing years of perfect payments across multiple accounts communicates recovery and stability. This pattern becomes visible to both algorithms and human reviewers operating beyond the credit score, creating approval opportunities even before older negatives age off entirely.

Why Monitoring All Three Credit Bureaus Matters

The reporting gap phenomenon creates significant score disparities across the three major credit bureaus because creditors selectively choose which bureaus receive their data. A creditor might report your account to Experian and TransUnion but not Equifax, or report to only one bureau to reduce their reporting costs. This selective reporting means your credit profile literally differs across bureaus—not just in minor details but in the presence or absence of entire accounts. When one bureau shows five positive tradelines and another shows only three, the resulting scores can vary by 50-100 points despite representing the same person’s creditworthiness.

These disparities create arbitrary advantages or disadvantages depending on which bureau a lender pulls during your application. Mortgage lenders typically pull all three bureaus and use the middle score, while auto lenders might pull only one bureau based on their preferred vendor relationship. If your Experian report contains a credit-builder loan and secured card that don’t appear on TransUnion, and the auto lender pulls only TransUnion, you’re evaluated on an incomplete profile through no fault of your own. The lender sees a thinner credit file than actually exists, potentially resulting in denial or higher interest rates based on information gaps rather than actual credit risk.

Bureau-specific error patterns compound this problem because each bureau’s data processing systems and creditor relationships create unique vulnerabilities to specific types of inaccuracies. Equifax has historically shown higher rates of duplicate account errors, where the same account appears multiple times under slightly different creditor names or account numbers, artificially inflating your reported debt and utilization. Experian’s systems sometimes lag in updating balance reductions, continuing to show higher balances for weeks after you’ve paid down accounts, which particularly affects utilization-sensitive scoring. TransUnion has demonstrated patterns of over-reporting credit inquiries, showing hard pulls that were actually soft inquiries or displaying inquiries beyond the standard two-year reporting period.

These bureau-specific vulnerabilities mean that monitoring only one bureau misses critical problems affecting your other reports. You might diligently track your Experian report, see no issues, and feel confident in your credit profile—only to discover during a mortgage application that your Equifax report contains a duplicate account error showing $15,000 in additional debt you don’t actually owe. The duplicate never appeared on Experian, so single-bureau monitoring provided false confidence while a significant error damaged your profile at another bureau.

The furnisher selectivity problem extends beyond major creditors to smaller lenders, medical providers, and collection agencies that often report inconsistently across bureaus. A medical collection might appear only on TransUnion because that particular collection agency has a reporting relationship with TransUnion but not the other bureaus. A small credit union might report your auto loan to Equifax and Experian but not TransUnion. This inconsistent reporting creates credit profiles that tell different stories depending on which bureau a lender consults, making comprehensive three-bureau review essential for complete error detection and accurate self-assessment.

The inconsistency particularly affects consumers building credit history, as positive accounts that could strengthen thin files may not appear on all bureaus. Someone strategically using a secured card to establish payment history might find that card reports to two bureaus but not the third, leaving one bureau showing an even thinner file than the others. Without checking all three reports, you cannot know whether your credit-building efforts are actually reaching all the places where lenders might evaluate you.

Dispute outcome variations demonstrate why identical disputes must be submitted to all three bureaus separately rather than assuming one bureau’s response applies to the others. The same dispute letter challenging an incorrect late payment can yield deletion at Equifax (which cannot verify the late payment with the creditor), correction to current status at Experian (which receives verification that the payment was actually on time), and verification of the original inaccuracy at TransUnion (which accepts the creditor’s inadequate response without proper investigation). Each bureau conducts its own investigation with its own creditor contacts and standards, producing different outcomes for the same factual dispute.

These variations create strategic implications for your overall credit profile management. When a dispute succeeds at one bureau but fails at another, you gain evidence that the item is indeed inaccurate—the bureau that corrected or deleted it implicitly acknowledged the error. This evidence strengthens subsequent disputes or escalations with the bureaus that initially verified the inaccuracy. You can reference the successful dispute outcome in follow-up letters, demonstrating that another bureau found insufficient verification for the same item. The variation also reveals which bureaus conduct more thorough investigations versus which ones rubber-stamp creditor responses, informing your approach to future disputes and potential legal action if patterns of inadequate investigation emerge.

Practical Steps to Build an Accurate Credit Profile

The comprehensive audit process begins with obtaining current credit reports from all three bureaus—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion—which you can access free annually through AnnualCreditReport.com. Pull all three simultaneously rather than staggering them throughout the year, as you need to compare reports side-by-side to identify discrepancies and ensure comprehensive error detection. Request reports directly from each bureau as well, as these often contain more detailed information than the consolidated versions available through the annual credit report service.

Systematically review each report section by section, starting with personal information accuracy before moving to account details. Verify that your name appears correctly spelled with no variations that might indicate mixed file errors, confirm your current and previous addresses match your actual residence history, and check that your Social Security number displays correctly with no transposed digits. Employment information should reflect your actual work history, and any unfamiliar names or addresses in the personal information section signal potential identity theft or file mixing that requires immediate dispute.

The account review section demands line-by-line examination of every tradeline, comparing reported information against your own records. Check account opening dates against your documentation—credit cards, loans, and other accounts should show the dates you actually opened them, not dates months or years earlier that might indicate fraudulent accounts. Verify that credit limits and loan amounts match your agreements, as incorrect limits artificially inflate utilization calculations. Payment history requires particular scrutiny—compare reported late payments against your bank statements and payment confirmations to identify any incorrectly reported delinquencies.

Often-overlooked sections include the inquiry list and public records area. Review every hard inquiry to confirm you actually applied for credit on those dates with those companies. Unfamiliar inquiries might indicate identity theft or impermissible pulls by companies checking your credit without authorization. Public records should contain only accurate bankruptcy, tax lien, or civil judgment information—many consumers discover outdated public records that should have been removed or records belonging to someone else with a similar name.

Common Credit Report Errors That Damage Your Score

Error identification requires understanding the seven most common credit report inaccuracies that damage scores and creditworthiness assessment:

Accounts belonging to someone else: Fraudulent accounts opened by identity thieves, or mixed file errors where another person’s account appears on your report due to similar names or Social Security numbers

Incorrect payment history: Late payments reported when you paid on time, or accounts showing delinquent during authorized forbearance or deferment periods

Wrong balances or credit limits: Current balances that don’t match your actual account status, or credit limits reported lower than your actual limits (inflating utilization calculations)

Duplicate accounts: The same account appears multiple times under different names or account numbers, artificially multiplying your reported debt

Outdated information: Negative items remaining beyond the legal reporting period (seven years for most negatives, ten for bankruptcies), or closed accounts still showing as open

Unauthorized inquiries: Hard pulls from companies you never applied with, or soft inquiries incorrectly reported as hard inquiries

Incorrect account status: Accounts showing open when you closed them, or paid accounts still showing balances owed

Building Effective Dispute Documentation

Each error type requires specific evidence for effective disputes. Accounts belonging to someone else demand identity theft reports filed with the Federal Trade Commission and local police, along with letters to creditors explaining you never opened these accounts. Incorrect payment history disputes strengthen significantly when you include bank statements showing payment cleared before the due date, or letters from creditors acknowledging billing errors. Wrong balance disputes benefit from recent account statements showing actual balances, while duplicate account disputes should reference the original account number and request removal of the duplicate entries.

Dispute letters should follow a clear format that identifies the specific error, explains why the information is inaccurate, and requests deletion or correction. Include your full name, current address,

The Complete Picture of Your Creditworthiness

The credit industry’s evolution beyond the credit score reflects a fundamental truth: that three-digit number was never designed to capture the full complexity of how you actually manage money. While traditional scoring models compress your entire financial life into one algorithmic output, payment patterns, utilization behavior, and alternative data points reveal creditworthiness that scores alone cannot measure. This shift creates genuine opportunities for consumers who’ve been unfairly penalized by reporting errors, thin credit files, or outdated negative items—but only if you understand what decision-makers actually see and take strategic action to build an accurate, complete credit profile across all three bureaus.

Your credit score doesn’t define your financial responsibility—it’s simply one imperfect measurement tool among many now used to evaluate risk. The real power lies in ensuring your credit reports accurately reflect your actual payment behavior, correcting errors that distort your profile, and recognizing that recent financial patterns matter more than a static number. When you shift your mindset beyond the credit score and focus on building genuine creditworthiness through accuracy and consistency, you take control of the narrative that truly determines your financial opportunities.