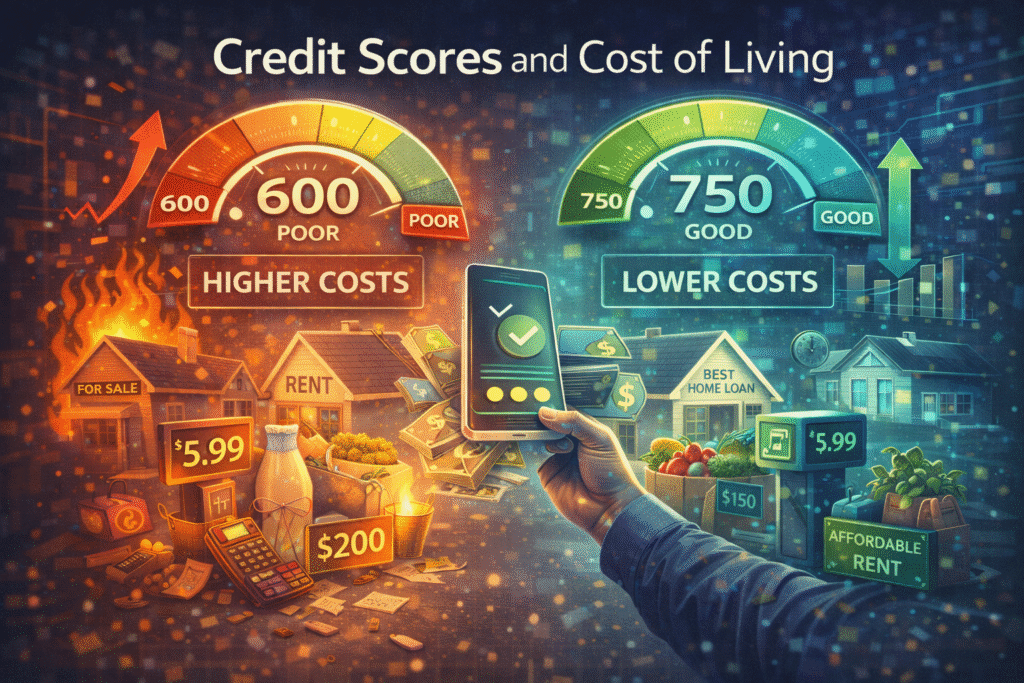

Your credit score might be dropping even if you’re doing everything right. Across the country, financially responsible consumers are watching their scores decline—not because they’ve changed their spending habits, but because the cost of everything else has. The reality of cost of living credit scores is that when your grocery bill climbs by 30% and your utility payments double, those same purchases that once fit comfortably within your credit limits now push you into different scoring territory. The connection isn’t always obvious at first.

What makes this situation particularly frustrating is that many of these score drops stem from two separate issues working against you at once, both tied to cost of living credit scores. Rising expenses force higher credit card balances and tighter payment timing, which legitimately affects your score. But there’s another factor at play: increased financial activity and account juggling during tight economic periods create more opportunities for reporting errors to slip through. These mistakes—wrong balances, misreported payments, outdated information—often go unnoticed when you’re focused on making ends meet, yet they can damage cost of living credit scores just as much as actual financial missteps.

The Utilization Trap: How Essential Spending Quietly Erodes Your Score

The credit scoring industry built its utilization benchmarks during economic periods that bear little resemblance to today’s cost environment, a mismatch that increasingly affects cost of living credit scores. The widely circulated advice to keep credit utilization below 30% originated from data analysis conducted when grocery costs, utilities, and basic necessities consumed a fundamentally different portion of household budgets. When your monthly grocery spending increases from $400 to $520 without any change in what you’re actually buying, that $120 difference doesn’t register in your credit report as inflation—it simply appears as higher credit card balances. The scoring algorithms interpret this increase identically to discretionary overspending, applying the same penalties regardless of whether you charged a vacation or vegetables, quietly eroding cost of living credit scores.

The mechanics of how credit utilization affects your score operate on two distinct levels that most consumers don’t fully understand, especially in the context of cost of living credit scores. Your overall utilization—the total of all your credit card balances divided by the sum of all your limits—receives significant weight in score calculations. However, per-card utilization ratios carry their own independent scoring impact. You can maintain a seemingly healthy 25% overall utilization while maxing out individual cards, and the scoring models will penalize both the high per-card ratios and the overall percentage. During inflationary periods, this dual-metric system creates a particularly insidious trap that disproportionately impacts cost of living credit scores. Essential spending concentrations—using one card for groceries and another for gas—naturally push specific cards toward their limits even when total available credit remains substantial.

Statement closing dates create another layer of utilization complexity that becomes especially problematic when cash flow tightens and directly influences cost of living credit scores. Your credit card issuer reports your balance to the bureaus on a specific date each month, typically your statement closing date rather than your payment due date. If your balance sits at $4,500 on a $5,000 limit when the statement closes—even if you pay it in full three days later—the bureaus record 90% utilization for that reporting cycle. Under normal economic conditions, consumers with stable cash flow can strategically time large purchases and payments to minimize reported balances. When inflation strains your budget, this timing flexibility evaporates, causing utilization spikes that damage scores regardless of payment intent or history.

The compound effect of rising interest rates adds another dimension to the utilization trap that receives insufficient attention in discussions around cost of living credit scores. When the Federal Reserve raises rates to combat inflation, credit card APRs climb accordingly—often reaching levels not seen in decades. Higher interest rates mean larger portions of your payments go toward finance charges rather than principal reduction. This forces balances to remain elevated longer, keeping utilization ratios high across multiple reporting cycles. Scoring models interpret these sustained high-utilization periods as financial distress, triggering score reductions based on algorithmic assumptions rather than actual financial management behavior.

The New Credit Cascade: When Survival Strategies Become Score Liabilities

The proliferation of alternative payment methods during recent years created an illusion that consumers could navigate rising costs without impacting traditional credit scores. In reality, many of these tools have quietly reshaped cost of living credit scores rather than protecting them. Buy-now-pay-later services marketed themselves as credit-neutral solutions, promising consumers the ability to spread payments across weeks or months without the scrutiny of credit card applications. The reality proved far different. Many BNPL providers now conduct hard credit inquiries before approving larger purchases, and several have begun reporting payment activity to credit bureaus. Each inquiry shaves points from your score, and the addition of new accounts—even installment accounts with small balances—affects your credit mix and average account age. Consumers who adopted BNPL as a strategy to manage grocery costs or utility payments without increasing credit card balances discovered they had simply shifted the pressure onto cost of living credit scores rather than avoiding it.

Balance transfer attempts represent another well-intentioned strategy that frequently backfires during periods of economic stress, further complicating cost of living credit scores. The logic appears sound: consolidate high-interest debt onto a new card with a promotional zero-percent rate, reducing monthly interest charges and freeing up cash flow. The execution, however, triggers multiple simultaneous score penalties. The application generates a hard inquiry, and opening the new account immediately reduces your average account age—a factor that carries substantial weight in scoring calculations. During the transfer period, both the old and new accounts may show high balances simultaneously until the transfer completes and creditors update their reporting. If you close the old accounts after transferring balances, you eliminate their available credit from your utilization calculations, potentially increasing your overall ratio despite reducing your total debt.

The average age of credit accounts operates as a long-term scoring factor that many consumers sacrifice unknowingly when adapting to rising expenses, a pattern increasingly reflected in cost of living credit scores. Opening a store credit card to access a 20% discount on groceries or household essentials seems like prudent financial management when every dollar matters. That new account, however, permanently alters your credit profile’s age calculation. If you’ve maintained credit accounts for an average of eight years, adding a new account immediately reduces that average. The impact intensifies with each additional survival account—a gas station card for fuel rewards, a home improvement store card for necessary repairs, or a medical credit line for healthcare costs. Collectively, these decisions signal financial stress to scoring algorithms, suppressing cost of living credit scores long after the immediate pressures fade.

Inquiry accumulation creates visible evidence on your credit report of financial strain, even when obligations are being managed responsibly—a dynamic that further weighs on cost of living credit scores. Rate-shopping for better insurance premiums, refinancing attempts to reduce monthly payments, and apartment applications during moves to more affordable housing all generate credit inquiries that cluster on your report. While scoring models recognize rate-shopping windows for mortgages and auto loans, they offer no such accommodation for the broader inquiry patterns common during economic adaptation. A report showing inquiries from insurers, landlords, utility providers, and multiple credit card applications within a short period is often interpreted as desperation rather than prudent financial management, resulting in cumulative score reductions that linger for years.

The Payment Timing Crisis: When Cash Flow Gaps Meet Rigid Reporting Cycles

Credit scoring systems operate on binary thresholds that fail to account for the nuanced realities of payment timing during periods of financial strain, a core issue behind declining cost of living credit scores. The most consequential threshold sits at 30 days past due—the point at which creditors typically report late payments to credit bureaus. A payment submitted 29 days late generates no credit report entry and no score impact. A payment submitted 31 days late triggers a notation that can reduce your score by 60 to 110 points and remains on your report for seven years. This cliff-edge structure makes no distinction between a consumer who forgot a payment and one who scrambled to gather funds but missed the reporting deadline by 48 hours, worsening cost of living credit scores during tight financial periods. The economic pressures that force payment delays—waiting for a paycheck, juggling which bills to pay first, dealing with unexpected expenses—receive no consideration in the scoring calculation.

The credit reporting system’s treatment of partial payments reveals another fundamental disconnect between algorithmic scoring and real-world financial management that directly affects cost of living credit scores. When cash flow tightens, many consumers adopt a triage approach: paying something on every account to demonstrate good faith and maintain relationships with creditors, even if they can’t pay the full amount due. From a practical standpoint, paying $75 on a $150 minimum due represents responsible behavior under difficult circumstances. The credit bureaus and scoring models, however, make no distinction between partial payments and no payment at all. If you don’t meet the minimum payment requirement, the account registers as unpaid for that cycle, offering no protection to cost of living credit scores.

A single late payment during a financially tight month creates cascading consequences that extend far beyond the immediate score drop and compound the damage to cost of living credit scores. Once an account shows a late payment, creditors often respond by increasing interest rates under penalty APR provisions, sometimes jumping from promotional rates in the teens to penalty rates exceeding 29%. The increased interest charges consume more of each subsequent payment, slowing principal reduction and keeping balances elevated. Some creditors reduce credit limits after late payments, immediately increasing your utilization ratio even if your balance remains unchanged. Late payment fees—typically $25 to $40—add to your balance, further increasing utilization and requiring larger payments to return to good standing. These compounding factors make future on-time payments harder to achieve, increasing the risk of repeated score damage.

Creditor reporting practices lack standardization in ways that create unpredictable score fluctuations, obscuring the true impact of cost-of-living pressures on cost of living credit scores. Some creditors report at the beginning of the month, others mid-month, and some at month-end. As a result, scores can vary by 20 to 40 points depending on when they’re pulled. A consumer under cash flow strain may appear overextended simply because balances were reported before income arrived. This lack of synchronization particularly disadvantages those who carefully manage payment timing, as their strategic efforts may be undermined by unfavorable reporting dates beyond their control.

The Error Amplification Effect: Why Financial Stress Exposes and Worsens Reporting Inaccuracies

The volume of credit account activity increases substantially when consumers navigate rising costs, and each additional transaction or interaction creates opportunities for reporting errors to enter your credit file—an often overlooked contributor to declining cost of living credit scores. Payment plan modifications, hardship arrangements, balance transfers, and increased creditor communications all require accurate data entry and transmission between multiple systems. When you contact a creditor to arrange a modified payment schedule due to temporary financial strain, that arrangement should be noted in their system and reported accurately to bureaus. In practice, these modifications frequently generate reporting errors—payments made under hardship agreements incorrectly marked as late, accounts showing delinquent status despite adherence to modified terms, or forbearance periods not properly reflected in payment history. Consumers who proactively address financial challenges often find their credit reports penalized, accelerating damage to cost of living credit scores rather than preventing it.

Negative information ages off credit reports according to timelines set by the Fair Credit Reporting Act, yet during periods of economic pressure, errors tied to cost of living credit scores persist longer than they should. When cost-of-living concerns dominate attention, credit report monitoring becomes secondary to immediate survival. Outdated late payments remain, settled accounts continue showing as delinquent, and bankruptcy notations persist beyond legal limits. These violations disproportionately affect consumers under stress, allowing inaccurate data to suppress cost of living credit scores for years after the original financial hardship has passed.

Balance misreporting becomes particularly common when consumers carry higher balances due to inflation, further distorting cost of living credit scores. Creditors may fail to report credit limit increases, show transferred balances twice, or miss payments made just before statement closing dates. While such errors occur even in stable times, their impact is amplified when legitimate balances are already elevated. A consumer whose real utilization is 45% may see 60% reported due to errors, triggering sharp score drops and potential credit limit reductions that compound the damage to cost of living credit scores.

The dispute process itself presents timing disadvantages that worsen score outcomes during periods of financial stress. Identifying, documenting, and disputing errors requires time, energy, and organization—resources in short supply when budgets are stretched. As a result, inaccuracies that hurt cost of living credit scores often remain unchallenged at precisely the moment they cause the most harm, influencing loan approvals, rates, and access to essential credit.

Mixed credit files and identity confusion become more common as consumers submit additional applications and engage in more transactions during cost-of-living crises, creating another hidden risk to cost of living credit scores. Variations in personal data, address changes, and overlapping identities can cause accounts to merge incorrectly or split across files. These errors can introduce delinquencies, unauthorized inquiries, and inflated utilization figures that are difficult to unwind. Consumers facing multiple financial stressors often lack the resources to resolve these complex disputes, allowing identity-related reporting errors to persist and compound score damage over time.

Strategic Report Review: What to Examine When Scores Drop During Economic Pressure

A systematic comparison of your credit reports from all three major bureaus—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion—reveals discrepancies that often signal reporting errors rather than legitimate negative information. Creditors are not required to report to all three bureaus, and many report to only one or two, creating natural variations in your reports. However, when the same account shows different information across bureaus—different balances, different payment histories, or different account statuses—those inconsistencies frequently indicate errors. A late payment appearing on your Experian report but not on Equifax or TransUnion suggests the creditor may have misreported information to one bureau or failed to properly verify the delinquency. Score drops that manifest on only one or two bureaus rather than all three point toward bureau-specific errors in how information was processed or recorded rather than legitimate changes in your creditworthiness. This three-bureau discrepancy audit requires obtaining reports from all three bureaus simultaneously to ensure you’re comparing the same reporting period, then methodically comparing each account’s details across all three versions.

Payment history verification demands forensic-level attention to detail, matching your personal financial records against what creditors reported to bureaus. Begin by gathering bank statements, credit card statements, and payment confirmations for any accounts showing late payments. Compare the dates you initiated payments with the dates creditors claim payments were late. Payment processing delays—the gap between when you submit payment and when creditors credit your account—create legitimate disputes when creditors report late payments for payments you submitted before the due date. Identify payments that creditors may have misapplied to wrong accounts or wrong billing cycles, a common error when consumers hold multiple accounts with the same creditor. Examine whether any reported late payments occurred during periods when you had authorized payment arrangements, forbearance agreements, or hardship plans that should have prevented late payment reporting. Creditors frequently fail to properly code accounts under special arrangements, allowing their automated reporting systems to generate late payment notations despite your compliance with modified terms. Each of these scenarios provides grounds for disputes backed by documentation that can result in removal of inaccurate late payment entries.

Balance and credit limit verification requires cross-referencing your own records with reported figures to identify creditor errors that artificially inflate your utilization ratios. Review your most recent statements from each creditor and compare the balances and credit limits shown on those statements with what appears on your credit reports. Creditors should report your credit limit accurately, but some report only your highest balance instead of your actual limit, making your utilization appear at 100% regardless of how much credit you’re actually using. Others fail to update credit limits after increases, showing outdated lower limits that make your current balances appear to represent higher utilization percentages. Balance reporting errors occur when creditors report balances from the wrong billing cycle, include pending transactions that haven’t actually posted, or fail to reflect payments that cleared before the reporting date. During periods of high inflation when you’re carrying larger balances, these reporting errors can push your utilization from the 40-50% range into

The Bottom Line: Understanding What’s Really Affecting Your Score

The connection between rising costs and declining credit scores isn’t just about spending more—it’s about how decades-old scoring algorithms interpret financial behavior during unprecedented economic conditions. The reality of cost of living credit scores is that when inflation forces essential spending higher, cash flow timing tightens, and survival strategies require opening new accounts or carrying balances longer, the credit scoring system penalizes these adaptations as if they were reckless financial decisions. Layer in the reporting errors that proliferate during periods of increased financial activity, and you’re facing score drops that reflect neither payment intent nor actual creditworthiness. The system wasn’t designed to distinguish between a consumer in crisis and one managing responsibly through difficult circumstances.

What makes this situation particularly concerning is that these score drops create real consequences—higher interest rates, credit limit reductions, and loan denials—that make financial recovery even harder to achieve. You’re not imagining the disconnect between responsible behavior and a falling score. The ongoing challenges tied to cost of living credit scores raise a critical question: can the credit scoring system accurately measure financial responsibility in an economic environment it was never built to assess?